From the stone circles of the Neolithic through the glories of Rome and the Renaissance to the ravages of the world wars, Europe boasts a history of extraordinary richness. Alexander the Great, Einstein, Mozart, Julius Caesar and Napoleon – Europe’s past is full of figures and events that loom large in the popular imagination. But the popular imagination is, famously, not always accurate.

Myths and mix-ups

Scroll through this gallery to uncover some of the most common misconceptions about the history of Europe…

1. Medieval battles were unruly brawls

In popular depictions like Braveheart and Game of Thrones, medieval battles involve two screeching mobs hurtling towards each other on an open plain before colliding with a sickening crunch. These battles quickly devolve into chaos, with key characters engulfed by 360-degree fighting that blurs friend with foe. Hours later, the victors pick their way through an endless field of bodies – the enemy all but obliterated.

Pitched battles were not common in the high medieval period, with warfare primarily conducted via sieges, but when they did occur they were very, very different to the disorderly melees generally seen on screen.

First and most obviously, soldiers tried not to die, and hurling yourself full-speed into an enemy pike formation was a one-way ticket to corpse town. Secondly, breaking formation was a shortcut to defeat, so advances were generally controlled and initially only the front lines would fight. Thirdly, armour was heavy and exhaustion could be a death sentence, so sprinting over muddy terrain was a no-no.

Finally, some movies massively overstate scale – specifically death toll. Most battles ended with retreat, stalemate or surrender – not annihilation. England and France could hardly have fought the Hundred Years’ War if their armies had been decimated in the first afternoon.

2. Togas were regular Roman attire

The Roman poet Virgil described the Roman people as ‘gens togata’ (‘the race that wears the toga’), and in frescoes and statues the Romans would often depict themselves toga-clad. But this iconic garment was not everyday wear – it was worn by some Romans some of the time.

The toga was a status symbol to be worn by Roman citizens only (foreigners, slaves and exiles were not allowed), and it was often an impractical outfit that the average Roman avoided where they could. It was hot, heavy, impossible to keep clean and expensive both to buy and to launder – great for being seen in at the theatre and dreadful for almost everything else.

If you wandered down a Roman backalley in the 1st or 2nd century AD, you’d mostly see unisex tunics of varying length and colour, along with loincloths, sandals and belts. But if you attended an elite Roman dinner party or snuck into a meeting of the Senate, you’d see grandees in ostentatious togas of differing colour and cut. Teenagers draped in bedsheets heading to student toga parties are not aping the Roman on the street – they’re aping the upper crust of Roman society attending events of state.

3. Vikings had horns on their helmets

Just like pirates and cowboys, Vikings are standard fare at children’s birthday parties, but, just like pirates and cowboys, they were extremely un-child-friendly in real life. ‘Vikings’ literally means ‘raiders’ in Old Norse, and they’re best remembered for terrorising the coasts of Europe between the 9th and 11th centuries, burning villages and extorting mountains of gold at the tip of an axe.

The horned helmet is key to their enduring appeal: a fearsome and instantly-recognisable symbol that can be purchased at any reputable dress-up shop, and has absolutely no historical grounding whatsoever.

Adding horns to a helmet makes zero sense: it would weigh down the wearer, get caught in trees or enemy weapons and pose an unnecessary challenge to early-medieval blacksmiths. The trope didn’t emerge until the 19th century – many hundreds of years after the last longboat skidded up on a European beach. Archaeologists have only ever found two intact Viking helmets (pictured), and both were conspicuously horn-less.

4. The French army is only good at surrendering

This uncharitable trope has two main sources. The first is France’s infamous collapse in the face of Nazi aggression in 1940, when the German army waltzed around the Maginot Line and took Paris in six short weeks. The second is a 1995 The Simpsons episode in which a beret-wearing Groundskeeper Willie colorfully describes the French as ‘cheese-eating surrender monkeys’.

The phrase was then popularised in America by National Review columnist Jonah Goldberg, especially following France’s refusal to support the US in the Iraq War.

Unfortunately for the English, the Spanish, the Flemish, and all France’s other historic neighbors, it’s not even close to true. According to historian Niall Ferguson, France is the most statistically successful military power in Europe, with 109 victories, 10 draws, and 49 defeats – an imposing 65% win rate. The English love to trumpet their victories at Agincourt, Crécy, and Poitiers, but all three took place during a war France eventually won, and Napoleon sits alongside Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar in the pantheon of great military leaders.

Even the language of war is French: think lieutenant, reconnaissance, bayonet, camouflage, regiment, general, and many more.

The Spanish flu came from Spain

Today we remember World War I (1914-1918) as one of history’s greatest tragedies – an unprecedented global conflict that killed roughly 16 million people across four gruelling years. The Spanish flu pandemic coincided with the end of the war, and, although estimates vary enormously, probably claimed more than three times as many lives in under half the time.

Perhaps the deadliest natural event in human history, Spanish flu re-entered public life during the COVID-19 pandemic, when century-old photos circulated showing overflowing hospital wards, gauze face masks and signs imploring people to wash their hands.

Part of the reason the pandemic is less well-known is that, in wartime, nations like Britain, America and Italy strictly controlled news stories that might dent national morale and initially censured reports of the disease. Spain – neutral in World War I – had a comparatively free press, and its media covered the outbreak from the get-go, leading to the incorrect assumption that it was the pandemic’s county of origin. Spain is now unjustly tarred with the virus – solely because its journalists did their job.

Pirates made their victims walk the plank

Almost our entire image of pirates comes from a single 142-year-old book. Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1883 novel Treasure Island popularised treasure maps, peg legs and parrots on shoulders – none of which are rooted in history. Walking the plank features too, but goes back even further (it was first used in 1724 by Robinson Crusoe writer Daniel Defoe) and is similarly spurious.

Common pirate punishments included flogging and marooning (stranding someone on an island with a pistol and a single bullet), but pirates had places to be, and plank-walking was far too elaborate when you could simply toss someone overboard.

In the Golden Age of Piracy, real-life buccaneers like Blackbeard and Captain Kidd made short-lived fortunes plundering merchant ships in the Caribbean and beyond. But these brutal, rapacious men had little in common with the caricatures seen in cartoons.

Our favorite pirate trope is the pirate voice – because it’s obvious as soon as you think about it that 18th-century marauders did not sail the high seas bellowing ‘aaargh’, ‘yaargh’ and ‘gaargh’. As usual Treasure Island is the culprit – this time the 1950 film, in which actor Robert Newton (pictured) made the inspired choice to give Long John Silver an exaggerated English West Country accent.

Nazi Germany was mostly defeated by America and Britain

In the western world, the popular image of World War II is one of British resilience and American triumph. After France’s notoriously speedy surrender in 1940, plucky Britain (which included millions of troops from its empire) stood alone against the Nazi war machine until America rode in to save the day in 1941. Relations between the West and the Soviets quickly soured after the war’s end, so Western writers were slow to credit the war’s real ‘star’ – Russia.

The numbers speak for themselves. For most of the war, more than three-quarters of German firepower was deployed on the Russian front, and four million of the five million German war dead met their ends in the East.

In the west, D-Day and Dunkirk are the war’s totemic moments, but in the east Stalingrad (pictured) was perhaps a greater turning point. Hitler and Stalin threw countless divisions into an at-all-costs struggle to secure the city, often in temperatures far below freezing. The result was the bloodiest battle in human history, and the estimated 1.2 million fatalities outnumbers the total war dead of Britain and America combined.

When Roosevelt and Churchill met Stalin at the Potsdam Conference in 1945, America had suffered 418,500 fatalities (0.32% of its population), while Britain had suffered 450,700 (0.76%). Russia had lost 14.8% of its population – around 24 million people.

Medieval Europe was a Christian continent

From crusader knights marching on the Holy Land with crosses daubed on their uniforms to tonsured monks cloistered in their monasteries, Christianity suffuses the popular image of medieval Europe. It was the dominant religion of many of the era’s great powers – powers that would go on to export it across the globe – but it was far from the only religion to shape the European continent.

Swathes of Spain and Portugal spent centuries in Muslim hands as Al-Andalus, while paganism thrived in northeast Europe well into the 14th century. But it’s the Muslim Ottoman Empire – Europe’s great forgotten power – that’s most egregiously left out of the narrative.

Historian Marc David Baer calls the Ottomans “very much a European empire” and “the unacknowledged part of the story the West tells about itself”. For 500 years they subjugated southeast Europe, extending their dominion as far west as Hungary and twice sieging Vienna. Only in the late-19th century did their grip start to slip, allowing nations like Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Romania to emerge from beneath the imperial thumb. Ottoman mosques still dot Eastern Europe, particularly in countries like Albania where Islam remains the dominant religion.

Greek and Roman monuments were white

For centuries now, the white-marble aesthetic of the Greeks and Romans has been a byword for refinement and grace. From the Renaissance onwards, artists and architects have been building in their image – from the sensuous sculptures of Michelangelo to the solemn columns of the US capitol. These monochrome creations are considered by some to be art in its purest form – elegant, timeless and kept honest by the purity of unblemished stone.

There’s just one problem: the Romans and Greeks painted their monuments every colour of the rainbow. Their temples and statues were once lavishly decorated, but while the stone has survived the pigments have long since faded, giving rise to the colourless copycats so common in more recent times. This image shows the famous Augustus of Prima Porta statue, crafted by Greek sculptors in Rome in the 1st century AD, next to a replica with its probable original colour scheme. It doesn’t look quite so tasteful, does it?

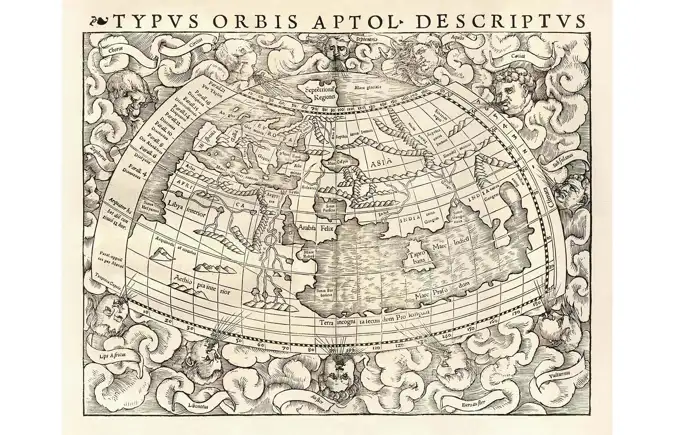

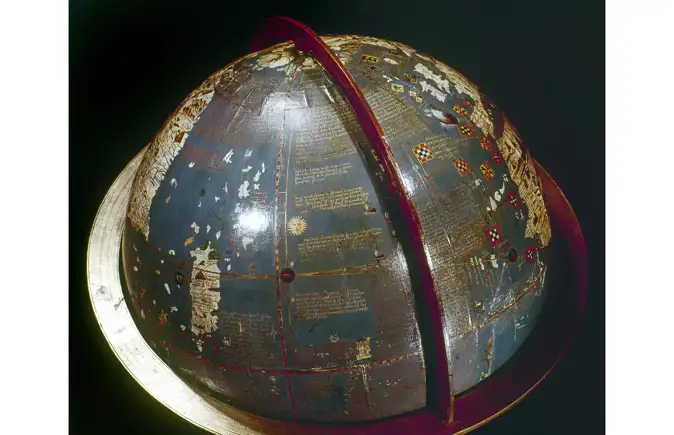

Medieval people thought the world was flat

It’s always tempting to think of our ancestors as ignorant and superstitious – it makes us feel more enlightened by comparison – but the great and the good of Europe have known the Earth was round for a very, very long time. Ancient Greek mathematician Pythagoras was arguing the case as early as 500 BC, while the legendary Greek philosopher Aristotle confirmed his claims 150 years later. Fast forward another century and another Greek, the astronomer Eratosthenes, had calculated the Earth’s circumference – and got it right within a few miles.

Pictured here is the Erdapfel – the earliest surviving globe, which misses out the Americas as it was made in Germany in 1492, the very year Columbus made landfall in the New World. Then as now, there may have been fringe elements banging the drum for Flat Earthism, but any medieval scientist suggesting the Earth was a disc would have been laughed out of the laboratory. Historian Jeffrey Burton Russell sums it up: “No educated person in the history of Western civilisation from the 3rd century BC onwards believed that the Earth was flat.”

Churchill said “we shall fight them on the beaches”

It was said of Winston Churchill that he “mobilised the English language and sent it into battle”, and his speeches, many of them preserved as crackly radio broadcasts, are almost as stirring today as they were in the 1940s. “We shall fight them on the beaches” is one of the most famous speeches of all time, but even the title is a slight misquote. The full line reads: “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.”

While we’re on the subject, Marie Antoinette never said “let them eat cake”; there’s no record of Gandhi saying “be the change you want to see in the world”; and Queen Victoria never said “we are not amused” – at least, not according to her family. Voltaire (pictured) also never said, “I disapprove of what you say but defend to the death your right to say it.” The line was a summary of his views written long after his death.

Finally, Julius Caesar did not exclaim “et tu, Brute” (“and you, Brutus”) while being murdered in 44 BC. The line first appears in Shakespeare, while Roman historian Suetonius has him uttering the Greek phrase “kai su teknon” (“you too young man”).

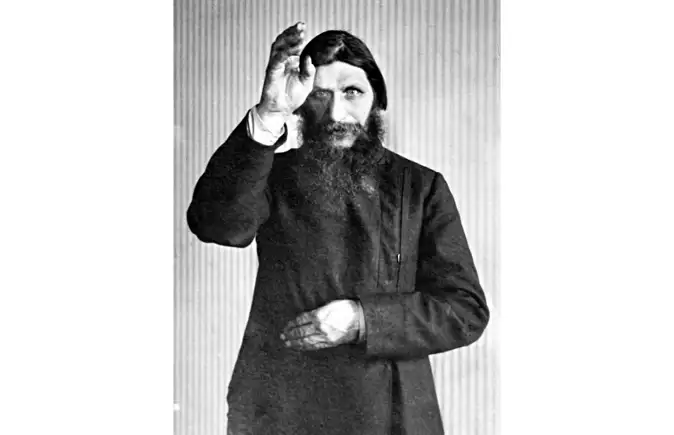

Rasputin had an affair with the empress and was impossible to kill

Immortalised by the Boney M song Rasputin, and as the fiery-eyed antagonist of hit films The King’s Man, Hellboy and Anastasia, Grigori Rasputin’s mythology still burns brightly more than a century after his death. A peasant mystic and faith healer, he became an unlikely advisor and confidante of Russia’s last empress, the Tsarina Alexandra, outraging Russian society in the run-up to the Russian Revolution.

Rumours swirled that his ecstatic rituals involved untold debaucheries with female devotees – and even that he shared the Tsarina’s bed. His influence at court eventually saw him assassinated in 1916 by disgruntled noblemen, one of whom later wrote that they’d had to poison him, shoot him repeatedly and throw him into a frozen lake to finally put him down.

The Boney M song leans into these lurid legends, calling him “lover of the Russian queen…Russia’s greatest love machine” and claiming that “they put some poison into his wine…he drank it all and said ‘I feel fine’.” But historians have widely dismissed claims that Rasputin and the Tsarina were having an affair, while his autopsy states simply that he was shot in the head at close range.

The song isn’t all wrong. The Tsarina certainly believed “he was a holy healer who would heal her son” (Tsarevich Alexei suffered from haemophilia), and “demands to do something about this outrageous man” did indeed get “louder and louder” as tales of his exploits spread.

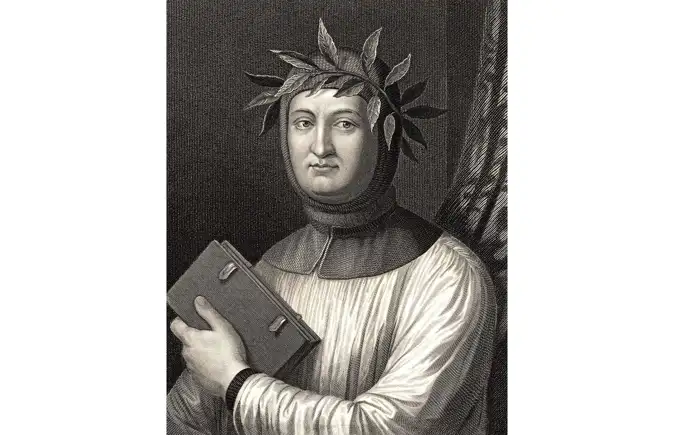

The Dark Ages were a time a primitive decline

There are few phrases that irritate medieval historians more than ‘the Dark Ages’. The term was first used by Italian scholars during the Renaissance – most notably by 14th-century poet Petrarch (pictured) – at a time of deep nostalgia for the perceived glories of ancient Rome.

‘The Dark Ages’, they argued, set in following Rome’s collapse in the 5th century AD, when barbarians ran amok and science and culture stalled. These scholars often visualised an almost literal ‘dark age’ – when the beacon of civilisation was extinguished, leaving Europe’s unenlightened inhabitants groping around for guidance.

Modern historians are unsurprisingly sceptical of any narrative that writes off 500-800 years of history. In reality, the early Middle Ages saw booming agriculture, the rise of an organised church and the foundation of the states that dominate Europe to this day. Just across the Mediterranean, the Abbasid Caliphate was enjoying the Islamic Golden Age – an era of progress in medicine, astronomy and mathematics.

Best of all, the Frankish kings of this period had invariably amusing nicknames. Good luck keeping a straight face in the courts of Louis the Do-Nothing, Charles the Simple or Pepin the Short.

Julius Caesar was born via caesarean section

The caesarean section was supposedly named after Julius Caesar, who had to be cut from his mother’s womb – presumably because he was too big and strong to enter the world naturally. The true origin of the name remains murky, but the story we can confidently debunk.

The C-section is a venerable practice – mentioned in antique texts ranging from Greek and Egyptian to Hindu and ancient Chinese – but it was not successfully performed on living women until the early 17th century. Caesar was born in 100 BC, and we know his mother Aurelia was alive and well when he invaded Britain 45 years later.

Instead, the story fits into an age-old tradition of attributing dramatic birth stories to heroes and kings. A thunderbolt is said to have struck the womb of Olympias before she gave birth to Alexander the Great (pictured), while Genghis Khan’s mother was supposedly impregnated by a beam of light. Legend holds that Greek mathematician Pythagoras was the son of the god Apollo, while the semi-mythical Chinese philosopher Lao Zi apparently popped into the world replete with a long, grey beard.

Benito Mussolini made the trains run on time

As far back as 1925, sympathisers were saying of Mussolini: “at least he makes the trains run on time”. Today, it’s a trope that simply will not die – despite being a fairly straightforward piece of fascist propaganda.

Benito Mussolini seized control of Italy in 1922 and ruled it with an iron fist for more than two decades, allying with Hitler’s Germany in World War II. With the war all but lost, he met a fate fairly typical for 20th-century fascist dictators – shot by partisans and strung up outside a gas station in Milan. A façade of authoritarian efficiency was central to his image, from the military to the economy – and to the railways.

In reality, Mussolini inherited one of Europe’s slickest rail networks – largely rebuilt by Italian State Railways general manager Cavaliere Carlo Crova after the ravages of World War I – and if anything made it a bit worse. Today, the wry aside that “at least he made the trains run on time” is used to suggest that some measure of good can come out of something otherwise bad. But amid the destruction of civil liberties, the list of war crimes and the torture and murder of political opponents, Mussolini’s Italy can’t even claim that.

Liked this? Share with Friends and Bookmark this website for more great stories